Balboa Park Skatepark Makeover And More

In this week’s newsletter, we cover proposals to improve Balboa Park and more.

Ingleside's library building turns 15 this year. But that doesn't mean there's not a whole lot of history behind it.

Ingleside’s decades-long struggle for a library culminated in its grand opening in 2009 thanks to its long-suffering and determined supporters. Some wondered that day if the building was large enough. But what now, after 15 years of an increasing and thriving business? What lies ahead for this little branch after the nearby Balboa Reservoir has been transformed into a new wing of Ingleside? Can we count on neighborhood and citywide stakeholders to advocate for expanded services?

The people of Ingleside pushed for a full-service library for decades.

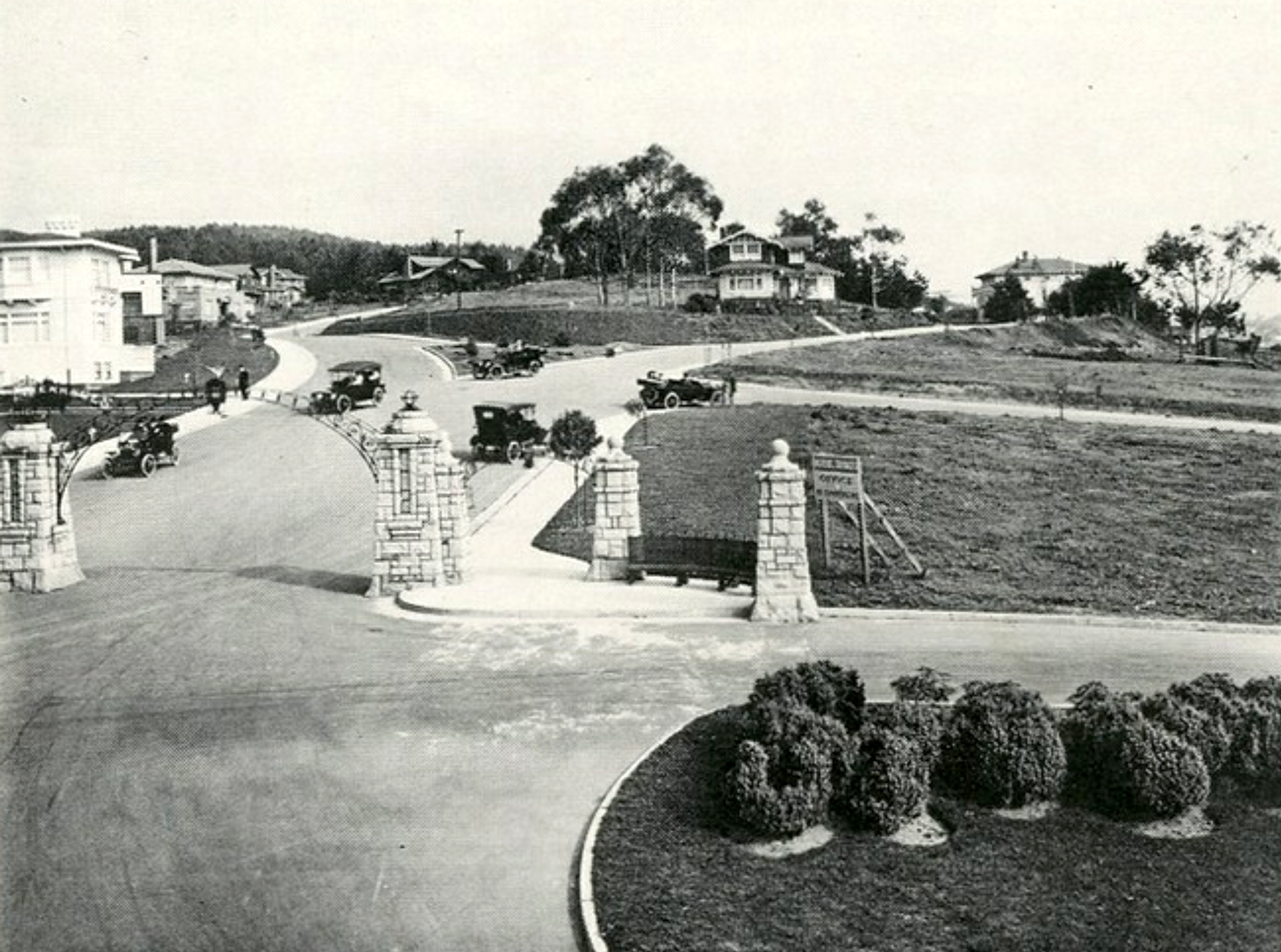

"Bloomsbury in London" was the model for the new community architect Joseph Leonard's Urban Realty Company planned for the 148 acres of the old racetrack. The new residence park would be called Ingleside Terraces. However, they weren't marketing to the people who used to hang out at the track. The "well-bred gentlefolk" and new homeowners being sought were told they'd be "twenty minutes via streetcar to the city center." ("The Panama Canal unites the Atlantic and the Pacific. The Twin Peaks Tunnel unites San Francisco and Ingleside Terraces,” one grandiose advertisement stated.) And these new residents would need amenities — like a real branch library.

Left: Ingleside Race Track enthusiasts in 1904. Right: Ingleside Terraces circa 1913. | Courtesy SFPL

The Ingleside Improvement Club started its campaign for library service in 1913 as well. But it wasn't until 1917 that a "Library Deposit Station" was finally set up at 422 Holloway Ave. It offered some books but no programming or reading room.

The Women's Club of Ingleside continued the demand for improved library services. In 1921, they were told once again that no city monies were available. The club approved $100 for the purchase of a table, chairs and shelving for the tiny deposit station anyway. In 1923, the Ingleside Improvement Club and the PTA from Commodore Sloat Elementary School joined forces to advocate for a better library, but their pleas were also denied.

"Europe cannot equal the beauty of the sunsets enjoyed by residents of the Ingleside Terrace" wrote Colonel F.F. Canon. He was a World War I veteran, who in 1925, worked for the Twin Peaks Realty Company. To further promote and advertise the development, Leonard and Holt, local realtors, planned to publish “House and Garden” magazine. It was to be 32 pages of eight-color lithography and would feature "a varied assortment of home plans.”

In addition to the views, other bragging rights included the K Ingleside rail line, which would "get you to Fourth and Market streets in 25 minutes" — up from 20 minutes. And more importantly, a branch library would be "close by."

Clifford S. Allred, one of the Ingleside Terrace developers, urged that an Ingleside Terrace library be housed in the new corner building on Ashton at Ocean avenues. In 1924 the developers initiated negotiations with the city about a rental space for the new branch. In late 1924 library trustees agreed and city staffers signed a 5-year lease, beginning January 1925, for $40 a month. Leonard and Holt handled the deal and sometime later, Jane Soldavini raised the rent to $125 a month.

Concurrently the Ingleside Deposit Station was moved — for one year — to 1612 Ocean Ave.

Finally, in 1925, the Ingleside Deposit Station moved to its new place at 387 Ashton Ave. It was officially elevated to Branch Library status which made it the eleventh in San Francisco's system. It received 1,217 new books for $1,825.50 and the phone number was JUniper 5-2680.

The Ingleside Branch Library remained at that leased location for an impressive 76 years.

The Ingleside Branch existed for the rest of the 20th century on Ashton Avenue. It weathered all the changes brought by World War II. And it survived failed library bond measures — which meant no improvements — in 1948 and 1953.

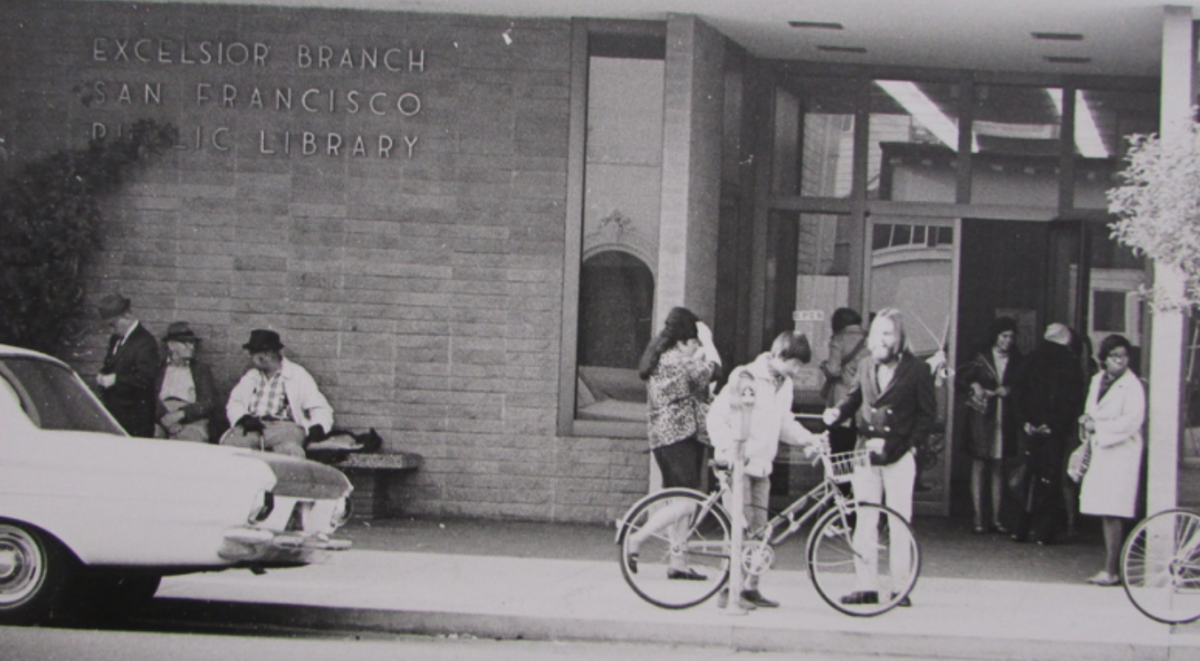

Big news in the 1970s was when the branch got "phono" records. But in 1972, when Joseph Alioto was mayor, members of the Friends of the Library and neighborhood activists formed a campaign called Keep Libraries Alive! This organized response was in reaction to the Library Commission's plan to close branches. By 1979, when Dianne Feinstein was mayor, city leaders were still threatening to close branches. Of the five, four of them were on the south side of town: Golden Gate Valley, Parkside, Portola, Ocean View and Ingleside. Proposition 13, which locked in property tax rates, was blamed.

In the 1980s, the Ocean View-Merced Heights-Ingleside Neighbors in Action was formed to help deal with the crime, juvenile delinquency, drug use, purse snatching and muggings in the area. And the nearby Farragut Elementary School was torn down for affordable social housing.

Ingleside Branch Library patrons pose for a photo in 1962. | Courtesy SFPL

The 1980s brought more drastic plans to demote some branches to reading centers — which offered a few books but no study space or programs — to deal with budget shortfalls. The branches on City Librarian John Frantz's list included Glen Park, Noe Valley, Visitacion Valley, Portola and Ingleside.

Feinstein directed the library commission to come up with a plan that would not depend on yearly budget increases. This led, in 1981, to the Lowell Martin Plan — named after the Columbia University library expert who penned it — that stated that the city has a lot of branches for the size of the city. Frantz said it was "repellent," but necessary, to close branches.

He explained the situation this way: "the Marina branch was built with the intention of having it replace the Golden Gate Valley branch. When the time came, people just wouldn't let us close Golden Gate." Library Commissioner Walt Jebe expanded on this by saying, “We don't like to do it […] but we have to stop wasting money on these unused branches.”

Ingleside's little library remained on the chopping block.

In 1982 Mayor Feinstein changed her mind after public outcry and found ways to increase the library budget so the Ingleside Branch stayed open. She wanted to establish a stable and permanent source of library funding and the Main Library was central to her vision for revitalizing Civic Center. She believed that adding hours and resources to the Main Library would lead to the diminishing use of the branches. This turned out not to be true for a variety of reasons.

The focus on the Main only galvanized support for the branch library system. Today the branch system remains an extremely important resource in the daily lives of San Francisco's residents. And the demise of downtown and arguments about the role of the Main Library continue.

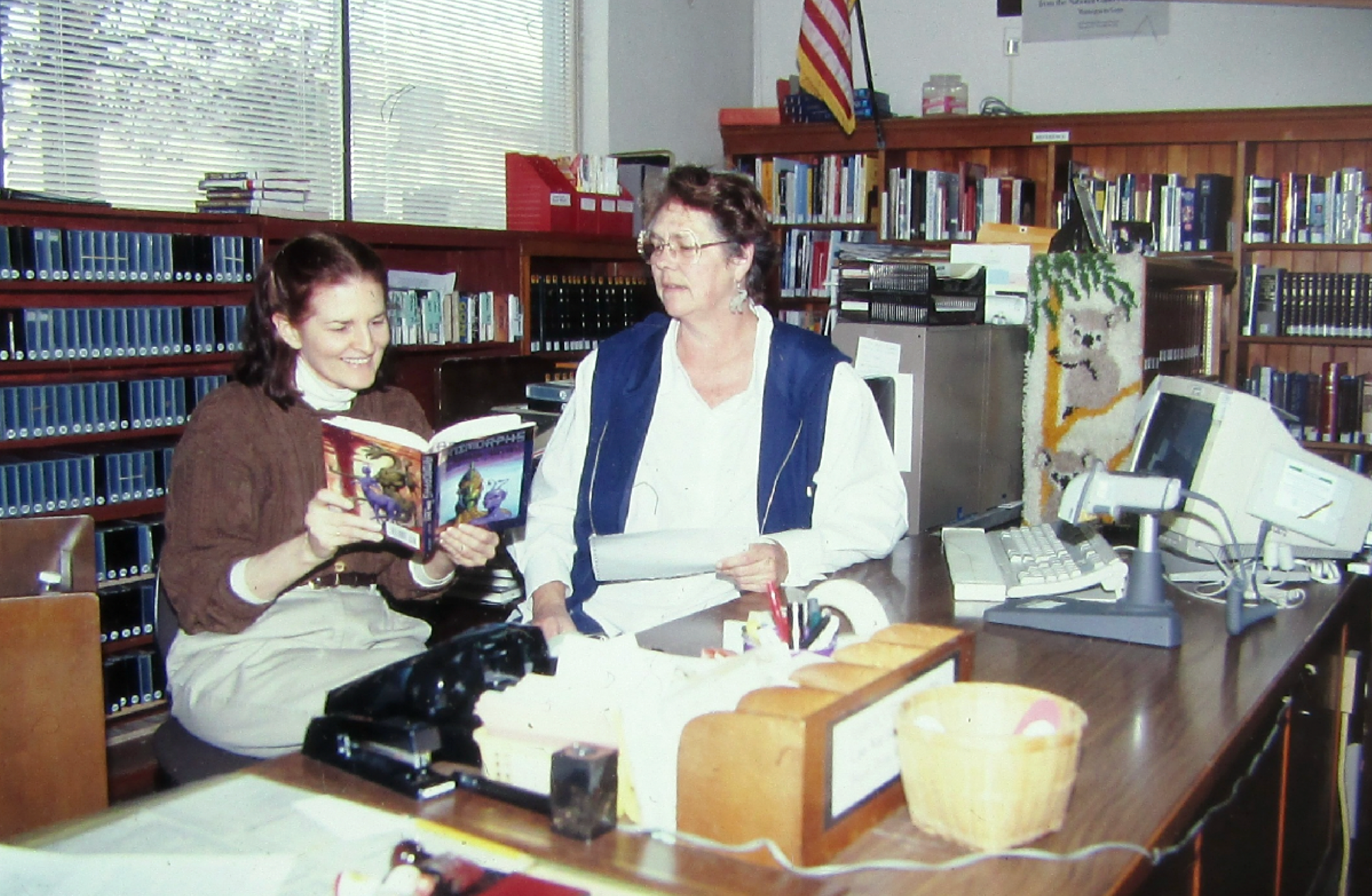

In 1988 Marie DeWitt, the Ingleside Librarian, announced that new technology would be arriving within two years. This was the beginning of the computer era in which we all now live.

In January 1988, Art Agnos became mayor. He was faced with a major budget deficit and proposed closing five branches. This mobilized voters in support of a Yes For Libraries campaign. In November 1988, Proposition A passed with 78% of the vote and the state bond measure also passed — but narrowly.

This made 1988 a fortuitous year for libraries. It was the first time since 1940 that San Francisco voters had passed a library bond measure. It was the beginning of an era when all library bond measures — like those in 1994, 2000, 2007 and 2022 — would be approved.

But Mayor Frank Jordan faced an even larger budget deficit when he took office in 1992.

The Ingleside Branch was closed temporarily in 1989 after the Loma Prieta earthquake. But it was soon reopened and faced a decade of changes. Next door there was a travel company, barbershop, mortgage company, and photocopy shop. Across the street was the Astronomical Society of the Pacific — founded in 1889 — which is still there today.

In 1994, the branch staff asked for better signage to direct people from Ocean Avenue around the corner to the branch. They wanted more shelf space, more open hours and more Chinese language and Spanish language books for their patrons. But once again, the branch was being threatened with closure.

The Library Commissioners at the time were James Herlihy, President; Virginia Gee, Barbara Rosenberg, Dale Carlson, Steven Coulter, Shepard Kopp and Roselyne Swig. Kenneth Dowlin was the City Librarian. They managed that year to find $728,000 in the budget to pay negotiated salary increases and benefits for library staff. But they too had a list of least-used libraries targeted for closure: Bernal Heights, Noe Valley, North Beach, Park, Parkside, Potrero, Glen Park, Golden Gate Valley, Portola and, not surprisingly, Ingleside.

Also in 1994, the Friends of the San Francisco Public Library launched a campaign for a City Charter amendment dedicated to stabilized library funding. Proposition E, otherwise known as the Library Preservation Fund or the library's "set-aside," did not have the support of Jordan. But it passed with more than 70% of the vote and was renewed in 2022 with more than 80% of the vote.

Jordan did not have to close branches.

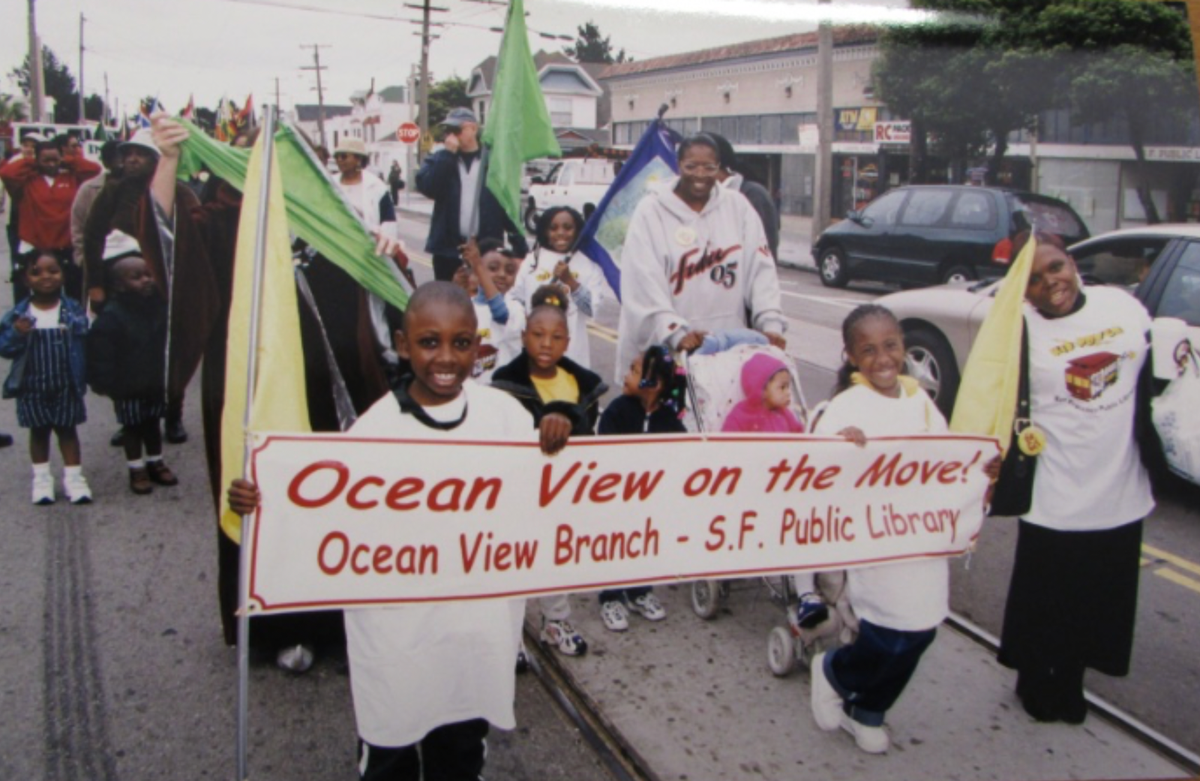

Acting City Librarian Susan Hildreth announced the opening of the brand new Ocean View Branch Library on June 7, 2000, during Mayor Willie Brown's second term. It was the first branch to be built in San Francisco since 1969.

That same month the citywide — not district — Supervisors Michael Yaki and Amos Brown introduced a major library bond measure. And later that year voters passed Measure A which eventually made possible the long-awaited Ingleside Branch Library.

The $129.2 million from A would be used to renovate 19 of 22 branches and it included seismic upgrades, disabled access and expansions. The budgets for the renovation projects ranged from $1.61 to $8.71 million per project.

Almost $15 million was designated for a support center at 190 9th St. and $5 million was dedicated to upgrade Brooks Hall — the Main Library's storage area.

The plan also called for six new buildings. The budgets for these new structures ranged from $4.78 to $6.88 million — $4.91 million was allotted for Ingleside.

The year 2000 was also when a plan was hatched to move the Ingleside Branch to yet another temporary site — this time on the main business strip of Ocean Avenue. Doug Moran, of the Friends of Ocean View Branch Library, championed the former Bank of America location as the perfect spot. He took Donna Corbeil, the chief of branches, on a walking tour and showed it to her.

On May 30, 2001, the Ingleside Branch Library reopened in the stately Bank of America structure at 1649 Ocean Ave. It was a leased facility but the new location greatly enhanced the library's visibility and accessibility and with 5,000 square feet of space, it was almost four times larger. It would remain there for eight years. And in lieu of a new building, this was better than nothing.

The new Ingleside branch was celebrated in its city-owned building in 2009. The Fougeron Architecture's structure of 6,100 square feet opened at 1298 Ocean Ave. — the former site of the Sunset Garage. It included a separate teen room, a separate community room with after-hours access, and a separate "egg-shaped" children's area with a window seat and skylight. John King, the San Francisco Chronicle architecture critic, wrote its design “sends an ambitious message that public buildings can strive to be civic landmarks.”

Lowell Martin, the library expert, stated in 1982 that public libraries suffered from an "overload of good works." Author, publisher, and former library commissioner Peter Wiley wisely noted that the needs of San Franciscans are "boundless" and while public libraries can play a significant role in meeting them, they cannot meet them all.

It's been 15 years since the new Ingleside branch opened. The need for and appreciation of it is as great today as it ever was. Its success has only revealed that the branch was actually too small the day it opened. Maybe it's time for an expansion? Or is this one of the needs that just can't be met?

Either way, the good news is, "we'll never have to move again."

We’ll send you our must-read newsletter featuring top news, events and more each Thursday.