Even after all these years, Juan Zhou Xu says she remembers every customer who has walked into Wang Wah, her family’s small restaurant on Ingleside’s Ocean Avenue.

“I might not know all their names, but if you tell me their favorite dish, I’ll know exactly who they are,” she said in Cantonese.

With little English, the petite and cheerful 69-year-old manages to bond with customers across cultures while taking orders and handing off to-go bags.

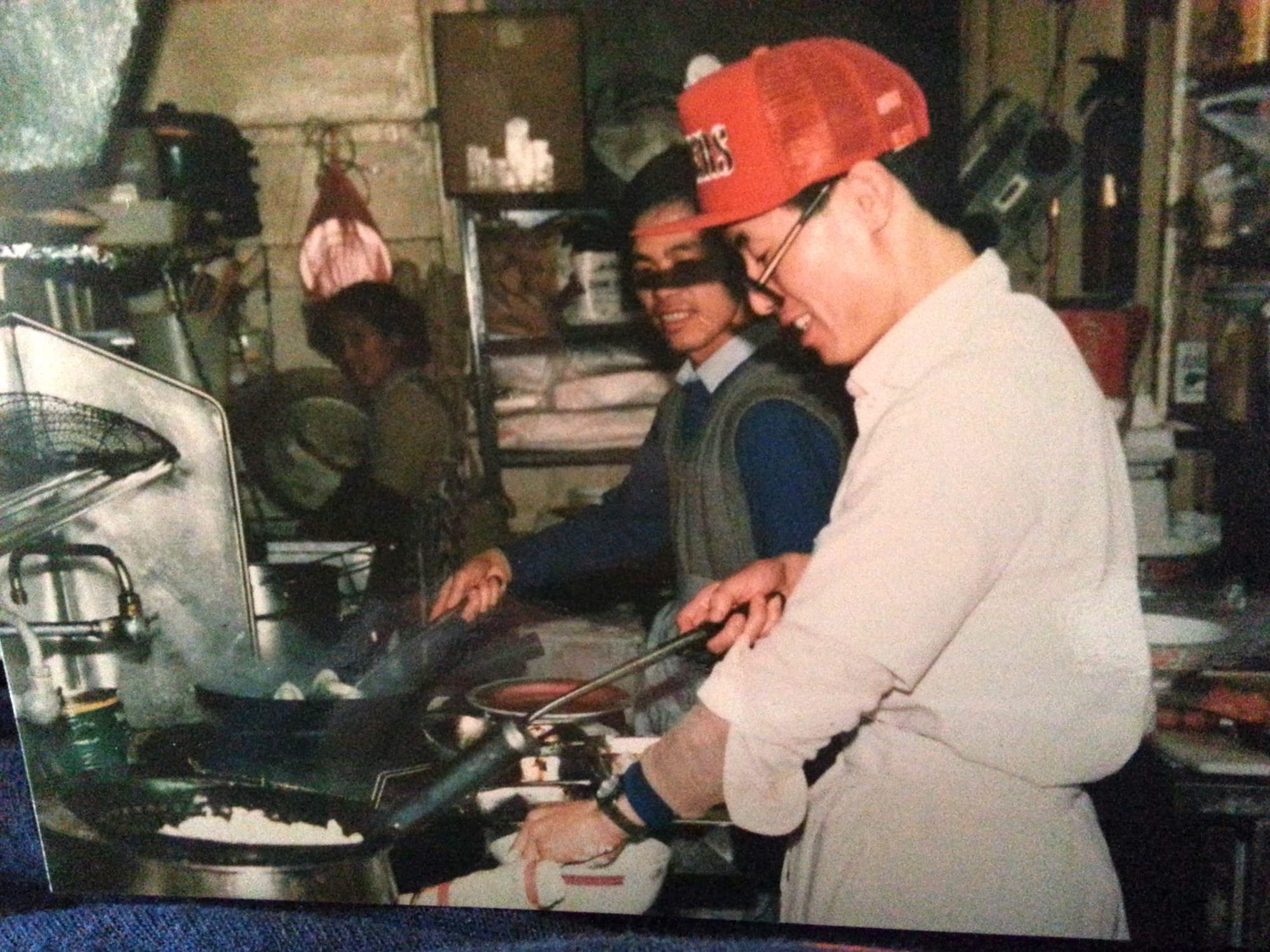

In the kitchen, her husband, Bing Xu, diligently prepares all of the dishes. The 71-year-old co-founded the restaurant 40 years ago, shortly after the couple married and he immigrated to the U.S. from southern China. Together, they quickly established a recipe for success in a gentrifying neighborhood.

The couple serves a menu of Chinese American classics — Mongolian beef to fried rice — that, Bing Xu says, are never cooked the same way twice because he matches the tastes of diverse customers.

“We are like a little United Nations,” he said. “People of all ethnicities come here for the food, yet essentially we are a place for the working-class people.”

Wang Wah is the oldest Chinese American restaurant in Ingleside, according to business records. When it opened in 1985, under the name Golden China, it was the only Chinese restaurant on a commercial corridor largely made up of African American-owned shops, bars and restaurants. Over the decades, the area has transformed as longtime residents moved out, and new ones moved in. The Xus led the way as other Chinese American businesses moved in.

The Xus say the secret to surviving 40 years in boom-and-bust San Francisco can be summed up in a Chinese saying, “薄利多销,” or “small profits, big sales.”

The cost of most menu items hovers around $14 and comes in generous portions. Bing Xu said that although the neighborhood’s demographics have shifted dramatically over the decades, one thing has remained constant: Wang Wah has always served people to get a filling meal without spending too much.

“I fell in love with the restaurant. The food was good and reasonably priced.”

“I’m addicted to her food; he cooks it, she sells it,” said Paul Dickerson while picking up wonton soup. He discovered Wang Wah three years ago and has been a regular ever since.

Marshall Berman first started going to Wang Wah in 1997, when he began teaching photography at City College of San Francisco.

“I fell in love with the restaurant,” he said. “The food was good and reasonably priced.”

Berman taught two classes a week, and stopping by Wang Wah for lunch soon became a ritual he looked forward to. Over time, the restaurant turned into an informal extension of campus life where he would hold office hours after class.

Now retired and living in the East Bay, Berman doesn’t come as often. But he still makes the trip back, drawn by the flavors he says he’s missed.

Taking Root in a New Place

The Xus grew up in the western reaches of Guangdong province during the Cultural Revolution, a time when the country’s political upheaval left little room for them to get an education. Bing Xu first moved to the U.S. in 1983 and, like many newcomers, landed in San Francisco’s Chinatown. His first job was in a grocery store, hauling bulk boxes up and down narrow aisles by day and taking English classes at City College in Chinatown after long shifts.

Once settled, Juan Zhou Xu joined him, and he began working in a Chinese restaurant that specialized in spicy cuisines from Hunan and Sichuan provinces.

In 1985, he partnered with a young Chinese American entrepreneur to open Wang Wah, timed with the opening of a new Walgreens in anticipation of the foot traffic the convenience store would bring.

Bing Xu spoke little English and struggled to communicate with customers. Yet when his partner left in 1987, he chose to keep the business. Juan Zhou Xu balanced work as a seamstress while taking English classes at City College and occasionally helping at the restaurant, where Bing Xu’s sister temporarily helped handle much of the communication. By 1991, Juan Zhou Xu joined Wang Wah full time and quickly became the public face of the restaurant.

At first, Juan Zhou Xu said she was nervous about taking orders over the phone, unsure if she would get it right. Yet her first regulars, mostly African American residents in the neighborhood, were patient and encouraging. Business was good.

“They would be like, ‘There’s no rush, take your time,’" she said. "Or sometimes would help me fix it when I made a mistake."

Over the years, the Xus built a loyal base of African American regulars, many of them city employees.

One of those longtime customers is 36-year-old ironworker Charles Winter. He first came to Wang Wah about a decade ago, after moving to the neighborhood from Bayview. His aunt and cousin, who already lived nearby, showed him around and brought him to Wang Wah. He has been returning for the food ever since, usually a few times a month.

“I don’t really like anybody else’s Chinese food,” he said, adding that his favorites include the chow mein and wonton soup there.

Serving Diverse Palates

San Francisco Heritage President and CEO Woody LaBounty remembered that when Wang Wah opened, there weren’t many Asian businesses on Ocean Avenue.

LaBounty, a former history columnist for The Light, said that since the 1940s and ’50s, many African American families had moved to San Francisco during World War II to work in the shipyards, later settling in the Ocean View-Merced Heights-Ingleside neighborhood as previous residents retired and moved out. By the 1970s, roughly two-thirds of the area’s residents were African American.

“Ingleside has always been that sort of revolving neighborhood with the new populations."

“Ingleside has always been that sort of revolving neighborhood with the new populations,” LaBounty said, explaining that the area’s smaller, more affordable homes made it an appealing entry point for immigrants and first-time buyers. Family-run Chinese restaurants like Wang Wah fit naturally into the neighborhood.

“It’s working-class food in a lot of ways,” he said. “It’s universal, something people always want. And you usually get a lot of food for the price.”

By the ’80s, a similar transition started to repeat. As longtime African American homeowners aged, many sold their houses and moved to East Bay suburbs such as Antioch, Hercules and Pittsburg. The new families moving in during the 1990s, and especially the early 2000s, were increasingly Chinese American, Chinese immigrants and other Asian households.

The Xus experienced the shift firsthand. Around that time, they left Chinatown and moved into a single-family home with their four children. Their clientele quickly changed as well: More Chinese residents moved into the neighborhood, and the construction crews renovating those new homes began frequenting the eatery.

“All of a sudden, lunch got really busy as Chinese American construction workers flooded in,” Bing Xu said.

New restaurants soon followed, from traditional Cantonese barbecue shops to seafood eateries. Unlike Wang Wah, these businesses primarily catered to the growing population of Chinese customers craving for dishes that feel closer to home. Bing Xu picked up on that trend of changing tastes and adjusted the menus.

“A lot of the Chinese here are from 四邑, the Sze Yup region, where we came from, including Taishan, Kaiping, Encheng and Xinhui districts,” Bing Xu said. “People from this area like stir-fried dishes or fish.” To meet those tastes, he added items like a catfish rice combo cooked in a traditional style, with the bones left in.

Today, the Walgreens that drew them to open to take a chance on Ocean Avenue is closed, and the Xus are at retirement age. However, they remain open and in service.

“I am working on it like it’s one of my hobbies,” Bing Xu said.

For Juan Zhou Xu, serving food has always been about more than work as well. It was also a source of joy. She enjoyed the casual but humorous exchanges with regulars.

“Back in the day, some Muni drivers would pull their buses right in front of the restaurant so I could hand them their food,” she said, laughing. “They tell me they can’t do that anymore.”

Wang Wah

Address: 1612 Ocean Ave.

Phone: 415-585-4953